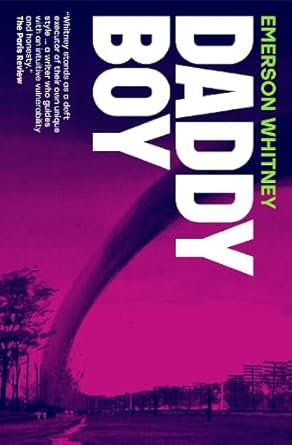

DADDY BOY

DADDY BOY

Couldn't load pickup availability

Mixing essay, queer theory, and memoir, a smart, big-hearted and electrifying exploration of masculinity, inherited trauma, queerness, love... and tornadoes.

After a decade-long relationship with a dominatrix he called Daddy, Emerson Whitney began to crave something besides submission. It came as a full surprise: submission had been so central to his early adulthood. Now what? Dizzied by new questions of transness and aging, living in a tent while his relationship ends, Emerson stumbles upon an advertisement for a storm chasing tour. 'For thrill seekers,' it says. Unsure what else to do, he signs up.

Daddy Boy follows Emerson as he packs into a van with a group of strangers and drives up and down America - staying in Days Inns and eating bags of carrots from Walmart and hunting down storms like so many white whales. Steeped in the prairie landscape of his childhood, Emerson recalls his adoptive dad, Hank, unflinching and extremely Texan; and his biological dad who, with his cowboy hats and puppies, always seemed so sweet and absent. From the van's trash-strewn backseat, and in the face of these looming figures, Emerson begins to wonder: Did he want to be Daddy now?

Paperback, 180 pages